Disclaimer: The following information is for educational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Always seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare professional.

Gastric lavage, also known as stomach pumping or gastric irrigation, is a medical procedure used to remove toxic substances or harmful ingestions from the stomach. While it was once a common intervention for poisoning, its use has significantly declined in recent years due to improved understanding of risks, more effective treatments, and guidelines that recommend against routine use.

Indications

- Acute Poisoning or Overdose: Gastric lavage may be considered if a patient has ingested a potentially life-threatening amount of a toxin within a relatively short time frame (generally within 1 hour of ingestion).

- Certain Specific Poisons: In rare cases, it may still be considered for ingestions of highly toxic substances that do not adhere well to activated charcoal, or when there is no effective antidote.

Procedure

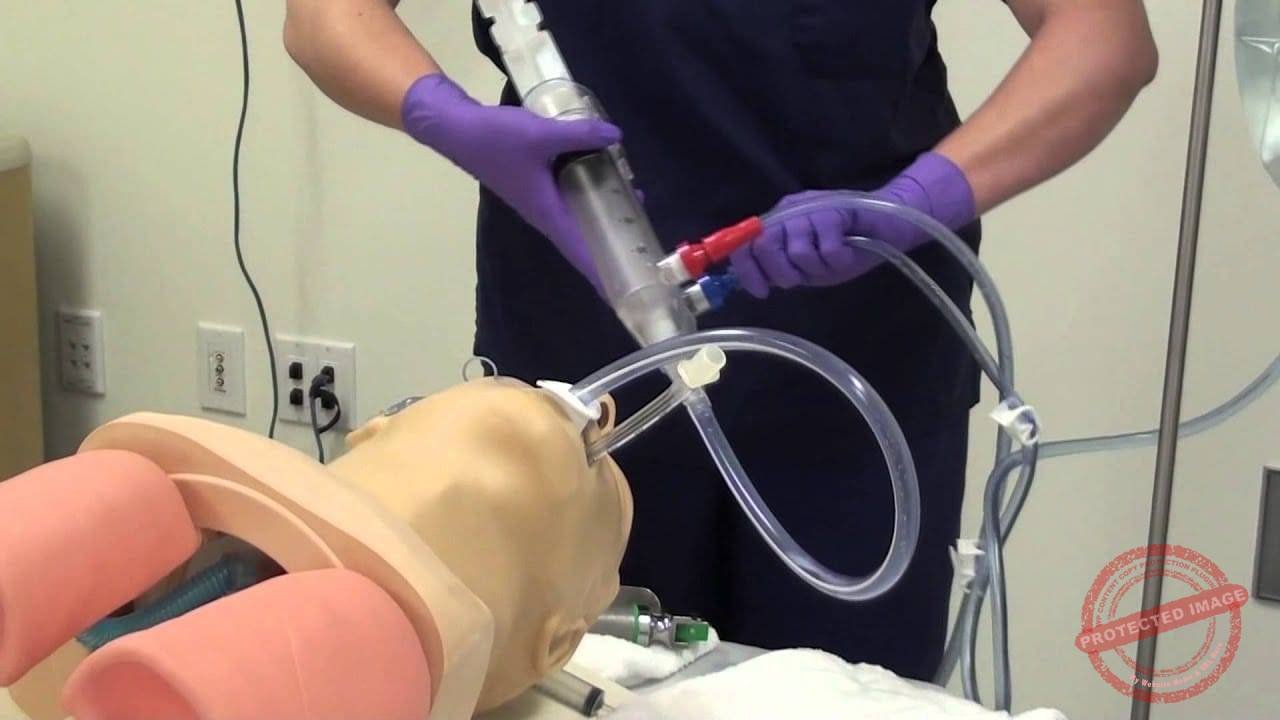

- Preparation:

The patient’s airway must be protected. In many cases, an endotracheal tube is used to secure the airway if the patient is unconscious or has a compromised gag reflex. - Insertion of the Lavage Tube:

A flexible tube is carefully inserted through the nose or mouth and advanced into the stomach. Proper placement is confirmed by auscultation, aspiration, or imaging. - Aspiration and Irrigation:

The stomach contents are first aspirated (suctioned out). Then, small amounts of warm saline or water are gently introduced into the stomach through the tube and re-aspirated. This process is repeated several times to help remove remaining toxic material. - Monitoring and Support:

Vital signs and airway patency are closely monitored throughout the procedure. Patients may require sedation or analgesia to ensure comfort.

Contraindications

- Caustic Substances: Ingestion of strong acids or alkalis, which can cause significant burns, is generally not managed with lavage due to the risk of perforation or further injury.

- Late Presentation: If the patient presents several hours after ingestion, most toxins have already moved beyond the stomach, reducing the benefit and increasing the risk of complications.

- Unprotected Airway: Patients at risk of aspiration (e.g., decreased consciousness without airway protection) may be at greater risk of complications if lavage is attempted without securing the airway.

Complications

- Aspiration Pneumonia: Accidental inhalation of stomach contents into the lungs can occur, especially if the airway is not adequately protected.

- Mechanical Injuries: Esophageal or gastric perforation can happen if the procedure is performed aggressively or incorrectly.

- Electrolyte Imbalances: Repeated instillation and removal of fluids can alter fluid and electrolyte balance.

Current Practice and Alternatives

- Limited Use: Guidelines from toxicology experts and poison control centers suggest that gastric lavage is rarely beneficial and should not be performed routinely.

- Preferred Methods: Activated charcoal is often more effective for many ingestions if given within a suitable timeframe. Specific antidotes, supportive care, and other treatments (such as whole bowel irrigation or hemodialysis for certain substances) are usually preferred.

In Summary:

Gastric lavage is a once-common procedure now rarely performed due to limited evidence of benefit and the risk of serious complications. Modern toxicology practice often relies on safer, more effective methods. If gastric lavage is considered, it should be done under strict medical supervision with careful assessment of the risks and potential benefits.